Editor’s note: A trigger warning before you keep reading: this essay is a true story about mental illness, sexual abuse, depression, and suicidal ideation written by a young woman who has just finished her first year of college. After trying many medications, she is doing transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for the first time. She chose to write the story under a pen name to protect her privacy. But every sentence is true. It’s also very hard to read. We are hoping that her struggle might help young people suffering from suicidal ideation or other mental health issues. And also help people learn about transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Editor’s note: A trigger warning before you keep reading: this essay is a true story about mental illness, sexual abuse, depression, and suicidal ideation written by a young woman who has just finished her first year of college. After trying many medications, she is doing transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for the first time. She chose to write the story under a pen name to protect her privacy. But every sentence is true. It’s also very hard to read. We are hoping that her struggle might help young people suffering from suicidal ideation or other mental health issues. And also help people learn about transcranial magnetic stimulation.

I’m 19 and Suicidal and Hoping Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Will Save My Life

By Astrid Lucas*

Special to JenniferMargulis.net

I can’t remember a period in my life without my mental illness. When I was five, after about a month of being sexually abused at school, I became preoccupied with feeling symmetry in my body. I would twist my hands and tap my fingers the entire day, waiting for it to feel “just right.” My family joked that I was ditzy and distracted. They didn’t know that I was afraid to eat or drink at school because I knew if I had to use the bathroom, there was a chance I would be trapped and abused again. My parents just thought I was just a slow eater.

In my fourth-grade class picture, I’m staring off to the side, my hands contorted awkwardly at my sides. I was still trying to get it “just right” so I didn’t feel indescribably off-kilter.

I was able to ignore the compulsions to tap and twitch a bit more as time went on. I distracted myself with schoolwork and sports. But I tended to obsess over those, too, especially over my grades. I retook standardized tests in elementary school until I was sure I had the highest score in the class. I still have no idea why my teachers allowed me to do that.

An anxiety disorder

In high school, I became so anxious about academics that I developed a full-blown anxiety disorder. Grades were the one objective, numerical way I had to measure my success. I was convinced one bad grade would ruin my chances of becoming a doctor. Adults in my life confirmed that academics were of utmost importance and their impact would follow me for the rest of my life. I did genuinely like school, but my scattered brain made it difficult to maintain straight A’s, and I would accept nothing less. Work that should’ve taken a few minutes would take me hours to complete, and I would procrastinate on everything out of stress.

I compared myself to everyone around me, and I always came up short. In the second semester of my first year of high school, it caught up to me. I was spending every free moment studying, playing soccer, swimming, or doing some sort of extracurricular activity. Because I was so busy, I had become estranged from my friends.

When swim season ended and a few clubs came to a close, I felt completely alone. I suddenly had what felt like all the time in the world, but I was still doing every assignment for school at the last minute. My days felt monotonous. I didn’t know that what I was experiencing was depression, but I knew that I despised myself. I criticized my grades, my looks, my social ineptitude, what I ate … everything.

Feeling constantly inadequate

I hadn’t really thought about my self-image before, but now I constantly felt inadequate. I felt like I was losing control. That summer, I constantly had to work to ward off feelings of inadequacy and hopelessness. I found relief from exercise and from scratching the skin on my legs with pencils or little broken pieces of plastic. When I was particularly stressed, I would jerk my head to the side in a little tic.

I convinced myself that once school started again, I would be too busy to be depressed. I was wrong. Although I distracted myself with sports and school, I felt like I was being followed, almost chased, by dread and panic. There was very little in my life to be actually stressed about—my parents both had good jobs, my family had plenty of money, we lived in a nice house in a safe town.

My uncle and grandma died, but I wasn’t very affected by it. In fact, I barely reacted to these events at all. When my grandma died, I felt nothing, then shame over feeling nothing, then relief that I felt at least a little bit shitty because of her death. I wondered if I was a sociopath. But I sobbed every night for a week after my parents sent our dog back to the shelter for behavioral and safety issues.

Making myself throw up for the first time

By the time I was sixteen, things had reached a tipping point. For the first time, suicidal thoughts entered my mind. I was overwhelmed in school and terrified of disappointing my parents in any way. I hated myself. I had certain foods that were “okay” in my mind, and certain foods that were unacceptable. Whenever I ate a “bad” food, I would be overcome with guilt. I had tried to vomit a few times, but it wasn’t until one night when my parents went out and ordered pizza for my siblings and me that it finally worked.

The first time I made myself throw up, I realized I had finally found something. I knew it wasn’t a good thing to do but at the same time, it made me feel okay when nothing else did. I scoured YouTube for videos on how to eat healthy and recover from disordered eating, but I didn’t really relate to their stories, which revolved around wanting to look good in a bikini or lose baby fat. Young men and women would talk about their eating disorders’ development, saying when they first purged they’d promised themselves it was a one-time thing. That was never the case for me. The relief I felt after that first time was almost euphoric. I finally felt like my body belonged to me.

That summer was the worst period of my life I had experienced. My eating went haywire and my mood dipped steeply. I went to bed each night with suicidal thoughts hoping I wouldn’t wake up and woke up each morning disappointed. I seemed fine to my friends and family, but I felt like I couldn’t hear anything over the suicidal noise of my own thoughts.

An artist’s depiction of suicidal thoughts. This is how I often feel. When psychotropic drugs didn’t work my therapist suggested transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Thoughts screaming in my head

I became afraid to drive alone because of the suicidal thoughts in my head screaming at me to crash the car so my death would seem like an accident. I tried telling a few friends about what I was experiencing but they didn’t seem to understand. I planned my suicide and would visit the spot periodically where I decided to crash my car.

I didn’t have a date in mind. But planning my death and fantasizing about ending my life was the only thing I could do to quiet the deafening thoughts. I felt like I was in an earthquake and screaming for help. But no one else seemed to be affected by the catastrophe I was certain would crush me. I was completely and utterly alone.

I didn’t see a way out until I joined water polo. I felt supported and loved by my teammates and playing water polo helped lift my mood just enough. I vowed to never again let myself get to the point of contemplating suicide and instead turned all my focus to food. Any time I had memories of what had happened to me in kindergarten or worries about the future, I would turn my thoughts to what I had eaten, what I hadn’t eaten, what I would eat, and when and how I would exercise.

I allowed myself very little food during the day, and as a result, my thoughts were constantly on food. I kept track of my calories by hand in a notebook and found comfort in the simple addition and subtraction I would do periodically throughout the day. I was losing weight and getting straight As, but I was terrified by the loss of control I would experience when I would binge and purge.

I tried to stop, but I was only able to make it a week at most before I would crave that feeling again of sudden relief from everything in my head that screamed at me. This pattern kept up and my weight fluctuated as my mood steadily declined. I was getting scared. I was losing control completely.

Senior year of high school

By the time senior year started, I was spiraling. I could barely keep my grades up. I had to leave class to have panic attacks in the bathroom, hyperventilating until I couldn’t see and hoping to God (or whoever) that this was the end. I was forcing myself to vomit multiple times a day, even when I hadn’t binged, and losing weight quickly.

I applied Early Decision to the college I now attend. I knew as I was writing my college essay about my devotion to nature and how I wanted to dedicate my college studies to protecting the environment that it was all a sham. I assumed I would not be alive to attend. I was so unhealthy that I would faint upon standing at least once a week. My vision would blackout during water polo practice. I had a persistent cough that kept getting worse.

My parents became suspicious of my eating habits. After smelling vomit in my bathroom one morning they started picking up little clues of what was really going on. I felt like the world was crashing in around me. I tried to keep everything to myself and make sure everyone at school and water polo thought I was doing fine.

One Wednesday, I typed up a summary of my depression and eating disorder and left it on my bed for my mom to find while I was hours away at a water polo tournament. When she read it, she realized that this wasn’t a month or two of disordered eating like she and my dad suspected, but years of secretive behaviors and lies.

Deeply ashamed

I was deeply ashamed of everything I had done and everything I’d hidden from them. My parents were sympathetic. They wanted me to talk to them so they could understand better and help me. But I felt as if I couldn’t tell them anything. I couldn’t bear the guilt and embarrassment.

Meanwhile, after admitting my eating disorder to my parents, I wasn’t allowed to leave the house alone, use the bathroom for an hour after meals, have my phone after 9:30 p.m., or go on water polo trips without my dad coming along. My parents had no idea what to do with me. I was still sick with a nasty cough, could barely sleep, and was extremely depressed. They were scared.

Things got worse. The cough for which I had refused to see a doctor for a month turned out to be walking pneumonia. I had been going to outdoor swim practice every day with pneumonia in the winter for a month. I stopped being able to make it through a full school day because of the fatigue.

Starting talk therapy

Thankfully though, I started going to therapy. My therapist was funny, empathetic, and empowered me to speak my mind. I started taking my first antidepressant: Prozac. I felt like a weight had been lifted off me, and when the Prozac started to work, I thought it would only get better from there. But the feeling of relief didn’t last long. I felt a bit better and started to eat more normally at first, but when I didn’t continue to get better, the lack of progress made me feel hopeless again. My doctor increased the dosage of Prozac but even that didn’t seem to work.

My parents took away the scales in our house. My doctor would weigh me backwards so I couldn’t see the numbers. At a dietician appointment, I saw my weight for the first time in weeks. I had gained four pounds. Those four extra pounds felt like twenty. I immediately started restricting my food intake even more and kept almost nothing down.

Over winter break at my grandma’s house, my parents watched, helpless, as I ran to the bathroom after every meal to force myself to throw up. I was suffocating in the guilt of what I was doing to my family, the money I was costing them for therapy co-pays and dietician appointments only to fail. I felt ashamed of the food I was wasting. But when I tried to cut back on my disordered eating behaviors, I would resort to banging my arms on desks and punching my thighs until they were covered in bruises. Eventually, I started cutting lines into my hips and ankles where no one could see.

I thought about death frequently and would go out walking at night in dark clothes, hoping to get hit by a careless driver. I closed my eyes on the highway for as long as my body would let me. The Prozac clearly wasn’t working.

The different psychotropic drugs weren’t enough to stave off my suicidal thoughts. Desperate, I eventually decided to try transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Trying another medication: Zoloft

After about three months, my doctor gave me two options: either add a low dose of an antipsychotic to aid the Prozac, or switch to Zoloft. I chose Zoloft. Zoloft worked better than the Prozac did at relieving my anxiety, which finally gave me some hope. But my sleep was still terrible, I was still passively suicidal, and I broke out in hives all over my body for two weeks from what my doctor could only assume was stress.

I gave permission for my therapist to tell my parents about the abuse I endured when I was little. When she told them they were devastated. They scheduled family sessions for the three of us and my dad sobbed through them, racked with guilt.

A second psychiatric medication: Trazodone

I kept getting respiratory infections because of my weak immune system and previous walking pneumonia and I missed a lot of school when my mood was just too bad to bear going. In short, I was still pretty miserable. That’s when my doctor and I decided to add a second psychiatric medication: Trazodone.

Trazodone is an antidepressant whose major side effect is drowsiness. For this reason, it is often prescribed to depressed patients to help with sleep. It helped me sleep and lifted my mood. It, along with the talk therapy, Zoloft, and brightening weather, made me feel more hopeful than I had in almost three years. I stayed on Zoloft and Trazodone for the summer, and although I wasn’t cured by any stretch of the word, I felt prepared for college. Because Trazodone is generally only recommended for up to six months of regular use, before starting college I decided to stop taking Trazodone and take a less intense medication, hydroxyzine. Hydroxyzine is an antihistamine that is sometimes used to treat anxiety.

The anxiety and trauma of starting college

Within a couple weeks of getting to college, a new wave of anxiety hit me like I’d never felt before. My panic attacks would last for hours and I would vomit involuntarily from stress.

Much of it stemmed from the relationship I was in with a boy I met during orientation and the sexual assault that had occurred just a month before classes started, although I refused to admit it. I convinced myself that the only reason I wasn’t sexually attracted to my boyfriend was the most common side effect of Zoloft, loss of sex drive.

Buspirone, which reduced anxiety and helped reverse the sexual side effects of SSRIs, seemed to be the perfect solution, and I added it to my regime. The person who prescribed it to me worked at the student health center, and the process by which he, a Physician Assistant, prescribed me medications was impossible for me to decipher. It involved consulting with a psychiatrist who was too busy for me to see directly. Nothing seemed to get better, even though I was still in therapy with my therapist from home and with a new therapist in the town where I went to college.

My therapist back home wondered if my boyfriend had predatory behaviors. I told her it just sounded that way from afar, and he was actually nice and sweet. I tried to convince myself the same thing, and even after he assaulted me, I told myself it was my fault. He apologized, and I pretended like I wasn’t beating myself up for it as we spoke. He seemed sorry. I told him I forgave him so we wouldn’t have to break up.

Emotionally detached

After this, however, I shut down completely. I detached myself emotionally from most everything and struggled with academics in college more than I ever had in my life. I broke up with my boyfriend but almost failed the class I was in with him. My thoughts were constantly racing at the closeness of his body to mine as we sat in our familiar seats next to each other. I would get flashbacks putting in tampons and end up sobbing for hours, barely aware of where I was.

When I went back home for a week over winter break, I told my doctor about the panic attacks I was having. She made sure I was going to therapy regularly, avoiding caffeine and alcohol, and getting enough exercise. Then she prescribed Klonopin as a short-term option to calm my panic attacks and anxiety enough so that I could learn how to cope with them without medication. Klonopin, a benzodiazepine and a cousin of Xanax, was only a short-term option for me because of its addictive properties. I could only take it for six weeks to make sure I didn’t become dependent on it. I used Klonopin for sleep for as long as I could but stopped taking it during the day after a week because it made me tired. Klonopin helped with my panic attacks, but so did going a month without having to see my ex-boyfriend.

Finding a psychiatrist

In the meantime, I found a psychiatrist in the Twin Cities, something my doctor made me promise to do before giving me a Klonopin prescription. As a substitute for Klonopin, she chose Clonidine, a blood pressure medication used off label for ADHD, sleep, and anxiety. Clonidine is also used to mitigate the effects of Klonopin withdrawal for those who become addicted. It didn’t work very well, so I upped my own dosage to over three times what I was prescribed just to be able to fall asleep at night and supplemented that with leftover previous medications when my prescriptions ran out.

By the end of January, I decided to report my ex-boyfriend to the school for sexual assault. I couldn’t stand seeing him wherever I went, avoiding the cafeteria if I knew he was there, and the athletic training room where he worked. The Title IX investigation through the school turned out to be a whole new type of hell. I would be virtually ignored for weeks at a time, and at other times have to sit in a room with a male stranger and explain every detail of the assault and the relationship.

My therapy was proving to be ineffective, as were my medications. Appointments with my psychiatrist were difficult to schedule. Instead, I bought razor blades at the drugstore down the street and put them to good use all over my stomach, which, as a swimmer, was the one place I could hide.

Suicidal again

I took random amounts of any medication I had on hand. At one point I took an entire bottle of buspirone. Going to sleep, I hoped I wouldn’t wake up. I did wake up though, in the middle of the night bent over a dorm toilet, vomiting my guts out and telling myself it was punishment for the stupid thing I had done.

I got extensions on some assignments, mediocre grades on others, and would regularly throw up from stress, as much as I tried not to. I stopped scheduling appointments with my old therapist to save time to do schoolwork. My friends tried to find places for me to sleep other than my single room so I wasn’t alone. My panic attacks returned, mostly at night, and would render me motionless and sobbing in my dorm for up to three hours at a time.

I looked up effective ways to commit suicide and got directions to the closest “suicide bridge.” I called a suicide hotline at 8:30 p.m. on my dorm floor eating a mug of oatmeal. I wrote goodbye notes to my friends, but when I tried writing to my family, I would burst into tears. I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t end my life knowing how much suffering I would put them through. I went to my psychiatrist and she increased my Zoloft dosage, which helped lift my mood a bit. But the Zoloft did nothing to help me work through the issues that were causing the low mood to begin with.

My birthday in mid-March was overshadowed by the looming threat of coronavirus and returning home. As miserable as I was in college at that time, there were good parts to every day and I felt supported by my close friends. I am also terrified of change. I had no say in the matter, though, and ended up back in Oregon a week after I turned 19.

My mom knew I didn’t want to be here anymore

Within two weeks of being at home, I was taking handfuls of ibuprofen every night hoping something bad would happen but feeling too guilty to kill myself outright. My mom called my therapist to describe how she “just knew” I wanted to die and could “sense” I “didn’t want to be here anymore.” My therapist told me about her conversation with my mom just after it happened.

I cried for hours every day alone because of how badly I wanted my life to end but how I knew I couldn’t do that to my family. I told my therapist and local psychiatrist I started seeing every week that I was desperate. I had reached a rock bottom I didn’t know existed. I had always thought suicidality was rock bottom. It’s not. The comfort of feeling like there’s some way out, even if it’s death by suicide, was calming compared to what I was feeling. I knew I was desperate, but I didn’t know what for. I didn’t know what I would do if it got any worse. I couldn’t verbally describe how I was feeling. My thoughts, all conflicting and arguing, wouldn’t let me say much at all.

I made an effort to go outside every day, even if it just meant sitting on my porch, but that didn’t always happen. I couldn’t visualize getting better, and all the medications I had tried that had failed me just solidified my belief that my brain was too fundamentally screwed up to ever change.

I also knew that my external circumstances could get far worse, and I felt that familiar guilt of feeling too bad when things are too good. That guilt, as always, made me want to implode.

Trying transcranial magnetic stimulation

My therapist could see how desperate I was. She suggested I try transcranial magnetic stimulation. I didn’t even question it, I just said I would try it. I would have tried anything at that point.

She explained the process to me and I felt a spark of hope. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a 6- to 8-week treatment, and I am at the end of my eighth week now. I go in 4-5 times a week and sit for twenty minutes with a helmet of sorts on my head. It delivers a series of magnetic pulses every few seconds.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation works by creating and exercising neural pathways to help the brain tear away from the familiar cycle of negative thoughts. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, and Major Depressive Disorder for those who have found several medications and therapies to be unhelpful or inadequate.

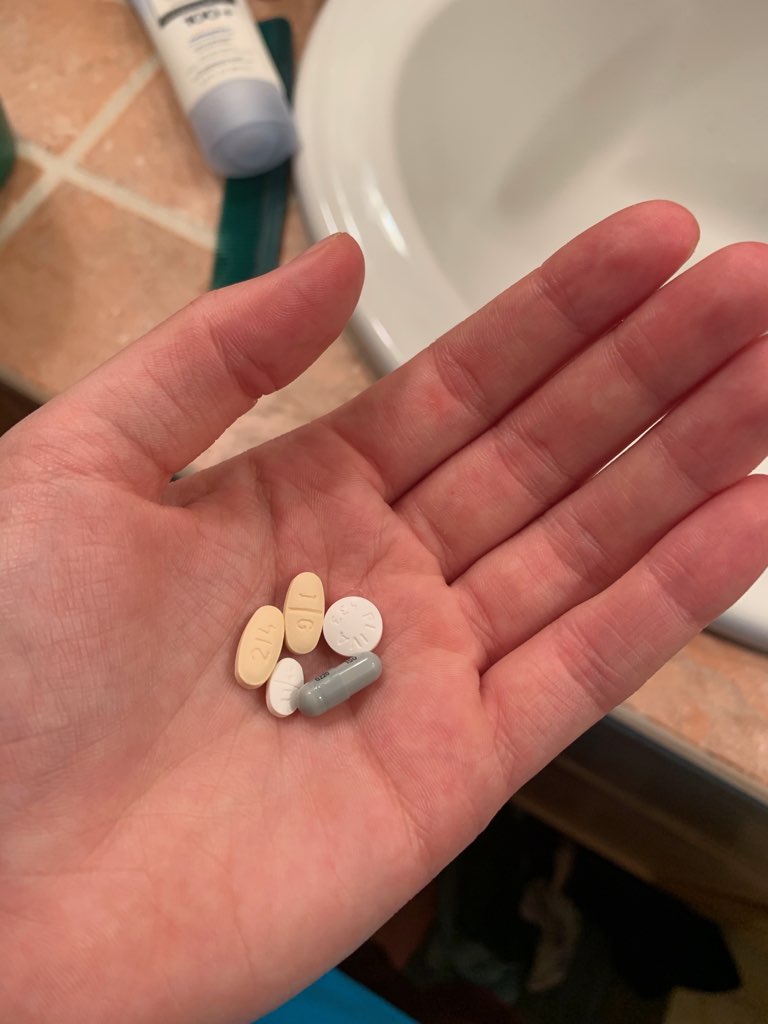

I added a small dose of lithium toward the beginning of my transcranial magnetic stimulation as well in order to curb the suicidal ideation. The transcranial magnetic stimulation took about four weeks to start working for me and I needed something to tide me over. Lithium is a mood stabilizer, normally prescribed for people with bipolar disorder, but in low doses it helps tremendously for suicidal thoughts and urges. I’m tapering off of it now, because, despite what my depression told me would happen, transcranial magnetic stimulation is working. I feel good, but not too good. I am also still taking Zoloft and Trazodone. But if my mood is stable for about six months, I will begin tapering off of them as well.

As part of a blood test I was given before the beginning of transcranial magnetic stimulation, I found out I am heterozygous for the 677T MTHFR gene, which plays a role in the metabolism of dopamine. It helps explain why I felt I had to use unhealthy coping mechanisms, like vomiting and self-harm, to feel better. B vitamins help people with this gene produce dopamine more normally, but I will still probably be on antidepressants for the majority of the rest of my life. That’s something I am trying to be okay with. I believe that they have helped save my life. The chemical issues in my brain may always be there, and I know that a lot of people take antidepressants long-term.

I wouldn’t be here today if it weren’t for therapists, doctors, and parents who took the time to listen to me and empathize. What is working for me, for now, is a holistic approach that includes exercise, nutrition, maintaining close relationships with family and friends, talk therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and my buddies Zoloft and Trazodone.

*Astrid Lucas is a pen name for a 19-year-old who has struggled with depression and suicidal thoughts. A sister, daughter, good friend, and excellent student, Astrid loves Oregon, backpacking, and mountain biking. She just completed her first year of college. She supports defunding the police. Read an update of her journey here.

MORE READING on this important subject of suicide, mental health and wellness during these troubled times:

Wow, this was so honest and brave of her! I hope it can help other people struggling with this.

At Epidemic Answers, we interviewed Robert Silvetz about transcranial magnetic stimulation a couple of years ago, and it was fascinating. There’s some really great research out there about it, and I’ve even seen ads in the Wall Street Journal for clinics using it for depression. Here’s the replay for the webinar: https://epidemicanswers.org/transcranial-magnetic-stimulation-autism-anxiety-depression/

Also, I wonder if she has PANS or PANDAS. Suicidal ideation is more common in kids with these disorders, which happens when a pathogenic infection (like strep, herpetic viruses, Lyme disease, etc.) crosses the blood-brain barrier: https://epidemicanswers.org/pans-pandas/

We also wrote a book about it; I hope she has time to read it! It’s called “Brain Under Attack”: https://www.amazon.com/dp/0692133275/ref=sr_1_1

If you have a way to contact this young woman, so she can read my message to her, I hope it can be done:

I share a very similar history. I am now 60.

All that rage you can’t seem to stop feeling against yourself needs to be turned on your perpetrators. Do not forgive them. Cut them out of your existence. They deserve no explanations. Nothing.

Sure they will try to keep invading your head, but first make the physical cut, and don’t look back.

Often the mother is also complicit in dad’s perverted activities, and will play the victim to block you from absolutely valid rage against her complicity, so she blocks you from being the real victim.

Disown them. Their betrayal of you and your justified horrendous rage against them is what you act out over and over. “Kill” them in your fantasies, go all out! Let your imagination run free and enjoy it!

The key is no contact.

It’s over.

You’re free.

Stay free.