When a friend commits suicide you can’t help but wish you could have done something to prevent it. Photo via Pixabay.

Kate Spade committed suicide. Anthony Bourdain committed suicide too. Their deaths made headline news. But when my husband’s best friend Mike committed suicide, it didn’t make the headlines.

My husband’s best friend committed suicide. Time stopped when James told me. My face went numb.

Mike? Not Mike. Was it a mistake? Had I misheard?

Mike did not die. Mike did not commit suicide. Not Mike.

Everything went quiet. I couldn’t hear the kids talking. Or the radio playing NPR.

It was like someone turned the volume of my life to off. Nothing existed but the words my husband had just said: “Mike died.”

My thoughts went quiet too. All I could think was there must be some mistake.

Mike Musgrove did not die. Not Mike.

All James could think about was why.

Why, why, why, James kept asking himself.

He sat at the table with his head in his hands.

He jammed his forehead with his fingers as if he could find the answer there if he tapped hard enough.

His shoulders shook as he cried.

“Why?”

Why would a man in his 40s with everything to live for shoot himself in the head?

Mike was always the best looking. The smartest. The soft-spoken unassuming blond guy with the offbeat sense of humor. Women adored him.

He had a eight-year-old daughter, the same age as our youngest. And when James went to visit him, just a few months before, Zoe helped pick out a present—a little plastic pony with a mane of golden hair—for James to bring back to our Leone.

Mike and James went to St John’s College together. After graduating he landed a coveted job as a journalist, reporting on the tech industry for the Washington Post. He got married to a beautiful, vivacious, successful woman who had an older son from a previous marriage. Mike bonded with his stepson. They played video games together, tried out tech gadgets it was his job to review. And then he had a baby of his own.

How could Mike—Mike—shoot himself in the head? What kind of unbearable heaviness was he feeling that led him to commit suicide, to kill the father of his only child, the friend of so many, the bright light that the world needed and wanted?

There had been layoffs at the Post when the economy took a dive. It was hard to find work. He probably drank too much. His relationship started to unravel.

“He must have been in so much pain,” I whispered, cradling my husband’s head in my arms. “He wouldn’t have done that if he hadn’t been in agony.”

Mike—we’re so sorry. We miss you so much. We ache for Zoe and Kim. We ache for the hurt that you felt, the isolation and disconnection, if that’s what it was. We want you to come back. We want you to be here. We want you to be the proud father who watches Zoe grow up, celebrates her college graduation, walks her down the aisle at her wedding.

We wish you had picked up the phone instead of that gun.

We wish we could turn back the clock and burst into your apartment that moment before you pulled the trigger and stop you from committing suicide.

It’s been almost a year since you died. It hasn’t gotten easier. We think about you every day.

In December James got suddenly and unexpectedly sick. We wished you were calling to cheer him up with your bad jokes.

“Death is something that happens to other people,” my 16-year-old daughter said. “It’s sad for them but not for you. You’re not sad. You’re dead.”

Perhaps that’s our solace. That dear, loved, sarcastic, brilliant Mike isn’t suffering any more, isn’t aching, isn’t unhappy. That he is at peace even as we are in chaos, shredded by his suicide. Shredded by our missing him.

My husband and dozens of Mike’s friends—he was that kind of guy, he had so many friends—flew to Maryland for the funeral.

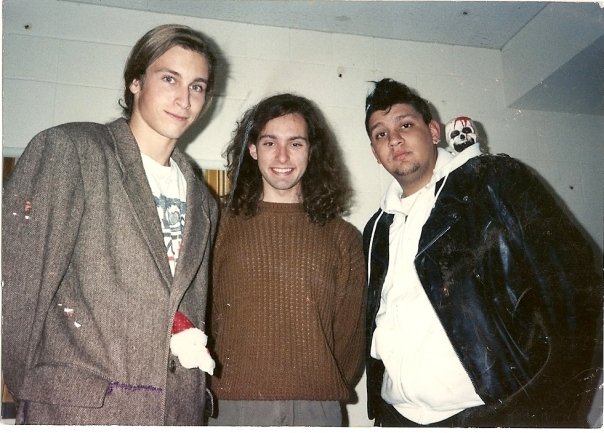

Mike (left) with James (middle) and Frank (right) at St. John’s College, around Christmas 1991

James gave this eulogy for Mike:

“Of the many people dear to us, most are ordinary people, some are unusual. You can’t call them unique because everyone is unique, and nobody we love is replaceable. Mike was an unusual person: witty, eccentric, offbeat, with eclectic tastes insatiable curiosity for the interesting things in the world. I guess what I want to say is that he was more unique than other people. Even his life experiences sometimes bordered on the surreal.

“When we started college, Mike was just 17, but he had already been to Santa Fe the year before, to stay in juvenile detention after an unplanned cross-country trip in a parent’s car. When they bailed him out, he saw the place sold T-shirts with CCA, for ‘Corrections Corporation of America,’ on them, and he bought one. Who buys a commemorative T-shirt from juvie? He wore it mischievously in college, amused when people thought it was for the local highbrow movie house, Center for Contemporary Arts.

“Once sophomore year a bunch of us from the dorm drove down to Albuquerque in one guy’s old station wagon because one of us, Adrian, wanted to get a piercing. It was 1991, so that was not only unusual, but, as it turned out, illegal in the state of New Mexico. So we end up finding a tattoo artist who will do it but not on the premises of the tattoo parlor, only if we went with him to his apartment. We get there and it’s one of those apartment complexes that looks like a motel, and when we go through the front door there’s a living room with nothing in it but a TV, a working motorcycle instead of a couch, his girlfriend sitting on the cycle watching said TV, and a bookcase with only one book on it: Mein Kampf.

“As the piercing commenced most of us drifted away squeamishly, but held it together until we got out of there. Mike got out the door and made it to the car, where he opened the car door and promptly fainted, smacking his head on the doorframe and sprawling on his back on the lawn. We crowded around him asking what happened and if he was okay, and he lay there looking up at the stars and said, “Let’s all have a little lie-down, shall we?”

“A lot of smart people are unusual, and it’s not easy to grow up that way. I want to acknowledge the hard parts of his life, too. St John’s got him to a better place, with people who got him, people he fit with. I lived with him sophomore year, and we had those endless hours of late-night conversations that make for deep friendship and are part of how we become who we are as adults. Yet even with me he sometimes found that there were things it was hard to talk about, with anyone. He came to Atlanta to live with me again one summer after college so he could write a novel. He spent every day at his desk writing and at 5 he would stop and open a 6-pack of Hamm’s and we would talk, I’d ask about the writing, and he would refuse to tell me anything about the book. At the end of the summer, he had finished the book and was heading back up to the Post, and I asked to see it—no judgment, just a draft—and he looked at me with a lopsided grin, shook his head once, just to one side: nope.

“It was hard to have spent his career at the Post, making senior reporter, and then lose his job as the Post imploded, and not be able to find work as a journalist again. Yet it was not long after that, when Zoe was a baby and he was home with her, that he called me as I was walking out of an airport and I stood in the sun talking to him for an hour, hearing that he was happy, unreservedly happy, for the first time that I had ever heard. It’s a joy I’ll never forget. I know the one thing in his life that was the most interesting, the most joyful, and the most important—it wasn’t that novel. It was his family.

“Mike will always be a part of me, an important part, very much alive in me and in all his friends, and in the years to come I want us to keep that alive and present for the kids, and I know he would want us to.

“This is the loss that has hit me hardest in my life. This is the saddest week in my life. And yet, amidst the tears, as I talk with the friends Mike and I shared, we keep getting into these stories about Mike, things he said, adventures we had with him, and laughing. He’s always going to be right here with me, and though I know that means that I will feel his absence, and want to reach out for more of him out there in the world, it also means he will be with me, bringing me laughter, and joy at the rich, strange wonders of this world, and gratitude that I shared it with Mike.” ~Love, James

RIP, Mike Musgrove. We’ll never forget you.

Published: February 14, 2018

Updated: January 19, 2020

Related posts:

Talking About Suicide May Help Prevent it

Do You Want to be Buried or Cremated?

If You’re in Pain, You’re Not Alone

My best friend left me 17 days ago. She was everything bright in this world. Reading this helped me.

Thank you.

I’m so sorry for your loss, Matthew. It’s so hard. For so long. ?